Today’s the Kentucky Derby. In the early days of the race, back in the early 20th century, Black jockeys dominated the field. What does WDKY in Lexington say about it today?

While no Black jockeys are riding in 2025’s Kentucky Derby, the jockeys riding in Derby 151 will either join the exclusive club of winning Derby jockeys or the even more exclusive club of multi-time Derby-winning jockeys.

So, I’m sure there were plenty of black jockeys in the 20th century, right?. Well, this Sports Illustrated story in 2023 said:

Historians say there were no Black jockeys in the Derby between 1921 and 2000.

Oh, OK. We’ll I’m sure that during its history, the Louisville Courier Journal stood up for the rights of Black jockeys, since as a socially conscious paper it was aware they were an integral part of the history of the event, right?

The Courier-Journal has been the paper of record for Derby coverage for the entirety of the race’s 148-year history. The coverage of Winkfield after each of his Derby victories lauded his riding skills while always making note of his ethnicity, as Black jockeys became more rare.

In 1901: “[A] little chocolate colored negro whose home is in Lexington.”

In 1902: “[A]s black as an ace of spades, and a jockey whose last two years of riding has won him money and reputation.” The paper that day hinted at Winkfield’s heroic status among Blacks, noting that as the jockey went through the paddock area on the way back to the jocks’ dressing room after the Derby, “he was followed by fifty or sixty colored stable boys. They were patting him on the back and fairly carrying him through the crowd.”

According to History.com:

But early in the 20th century, Jim Crow segregation laws throughout the South, combined with pressure from white jockeys, forced African American riders out of the “sport of kings” spotlight and into menial jobs as grooms and horse stall cleaners. White riders increasingly used violence on the track against their Black rivals.

“In the Jim Crow era, Black jockeys disappear,” says Chris Goodlett, senior director of curatorial and educational affairs for the Kentucky Derby Museum. “We’re often asked at the museum, ‘Where did Black horsemen go?’”

Surely, Churchill Downs is aware of this injustice, since this quotes the Kentucky Derby Museum (which is at Churchill Downs), and is doing all it can to get rid of the remnants of racism that have permeated the event for a century? Well, Smithsonian Magazine says:

When the brightly decorated horses leave the stables at the re-scheduled Kentucky Derby this weekend, they’ll parade to the starting gates to the familiar tune “My Old Kentucky Home.” …

Few of those singing along, however, may realize that the original lyrics were not a “Dixie”-esque paean but actually a condemnation of Kentucky’s enslavers who sold husbands away from their wives and mothers away from their children. As Foster wrote it, “My Old Kentucky Home” is actually the lament of an enslaved person who has been forcibly separated from his family and his painful longing to return to the cabin with his wife and children.

I’ve been to the Derby a couple of times. Paid thousands of dollars for seats. The last time I went, the people sitting in the box next to mine were downing Mint Juleps throughout the day, getting drunker and drunker by the hour until the actual Derby run happened late in the afternoon. And when the starting gate opened, they started vomiting.

I will never go to another Derby.

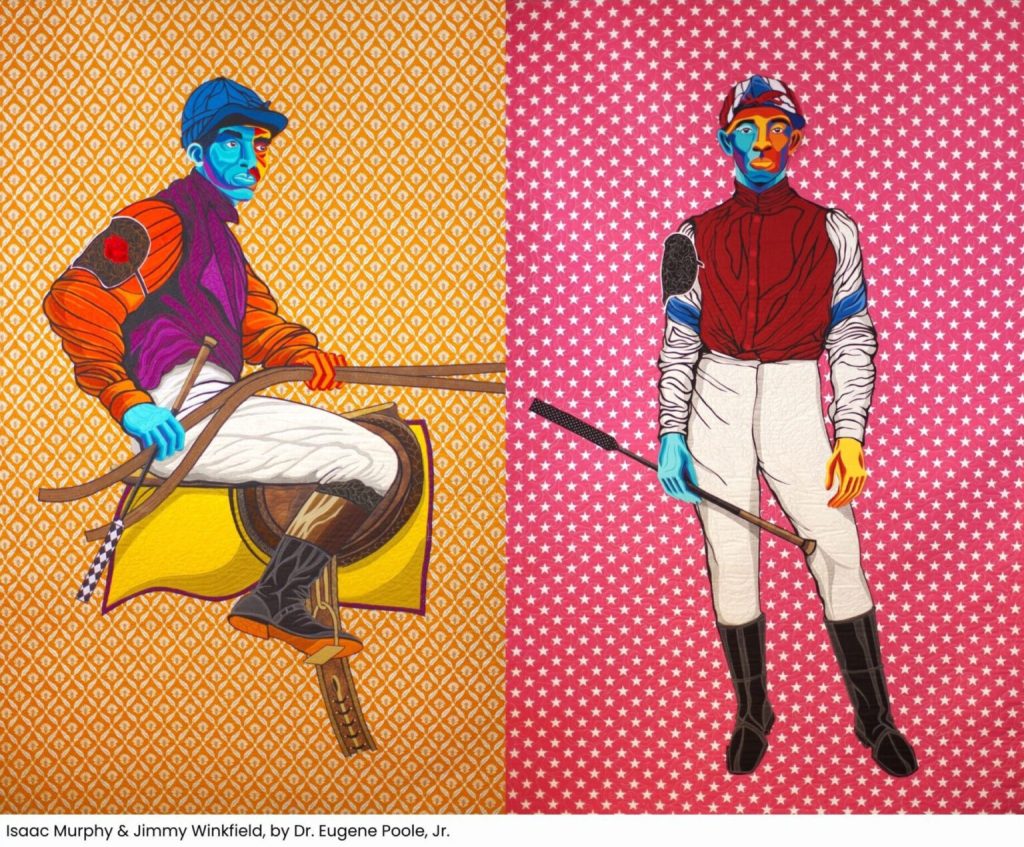

But I will recommend the art exhibit that features the images at the top of this post. It’s at the Kentucky Center for African American Heritage, and it’s entitled: The Quilts of Dr. Eugene Poole, Jr.: Reflections in Black. Kentucky Derby Jockeys, 1800s to 1900s. The exhibit features colorful quilts showing the top jockeys of the late 19th and early 20th century. And the individual quilts can be purchased, but the starting price is just above $8,000.

That’s about the price of a few nice seats at the Derby.

Leave a comment